Dimitris Yeros, Louise Bourgeois, New York, 2009

David Seidner, Louise Bourgeois, 1992

David Seidner, Louise Bourgeois, contact sheet, 1992

Louise Bourgeois

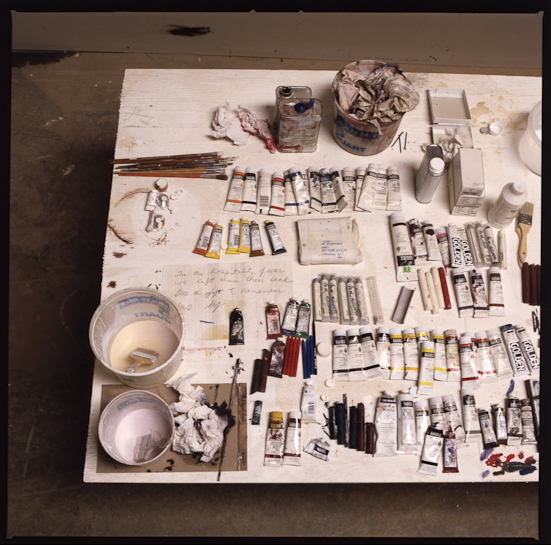

With all its contents, the studio that Louise Bourgeois occupies in Brooklyn is like a giant version of one of her installations. I entered a nondescript masonry building and was met by a bright white fluorescent-lit hallway—like an isolation chamber from the artist’s space. Once inside, I encountered the old foreman’s office from the loft’s last life. There, Louise now keeps her own office and watches over what goes on in the antechamber through a window. She hides in that cubicle until she’s ready to receive her visitors. A room off the main studio was bursting with decades of work. Rarely has the autobiographical manifestation of plastic form taken such a tangible human presence. There was a profusion of limbs, phallic tendrils, pistons, lumps, cylinders, and erections, in wood, plaster, marble, bronze, and latex—a dizzying maze of psycho-sexuality. When she emerged from her womb-like office, Bourgeois was tentative, coquettish, impossible. She did not strike me as a Surrealist. Rather, she has her own reality, a staccato stream of consciousness that goes in myriad directions at once. She seemed to speak in non-sequitors, so I stopped trying to anticipate any kind of logical conversation and simply deferred to her wishes. She was a bully until I seduced her by complimenting her work, talking about past museum shows and installations. Then, she became a docile little girl, smiling, almost blushing. I had been warned beforehand that she would want to take the film from the sitting. develop it, edit, and decide what would be the final print. So, to make sure I left with a portrait, I instructed my assistant to put a mason jar full of water in the trash bag in which we would put the Polaroid negative.

She saw the Polaroid and loved it, and began rearranging her collar, hair, and scarf. I only mention this because the woman seemed to have a total absence of vanity, but in true French fashion, was very concerned with the way she looked. I had been trying to photograph Louise for three years. When I originally called about doing her portrait for Beaux Arts magazine, I sent over a copy of a book of fragmented fashion photographs. She said, “The way you cut up women is phenomenally cruel and I will not subject myself to that!” And she hung up on me… Her energy was daunting I loved spending time with her in Brooklyn, and in her modest townhouse in West Chelsea where she seemed to have been forever… Given to philosophizing and grand proclamations, she told me that her favorite bedtime reading was Le Concept de l’Angoisse by Soren Kierkegaard. Her answers to questions at first seemed convoluted, but on closer inspection, revealed a razor sharp clarity. The answers turned and came back around on themselves, so that the answer and the question both became Bourgeois’ own doing. That seemed to me a fitting metaphor.

David Seidner, Artists at Work: Inside the Studios of Today’s Most Celebrated Artists, 1999, p. 34–41

Tagged: David Seidner, Dimitris Yeros, Louise Bourgeois